(Typical Enclosed Balcony - Exterior Facade)

They have either been the bane of one's ownership/renter experience, or sanctuary in a world of increasing noise in our urban environments. Solariums, or "private open-space amenities" (if a glass box that resembles a quarantine facility in one's living area can be considered "open space") were the once well-intentioned plans to encourage balconies in the construction of new buildings throughout Vancouver. With a significant percentage of their footprint excluded from a site's FAR calculations, the City has since created a building typology that subverts its original intentions and instead brings homogeneity and 'private closed-space tragedies'.

Recently attending the 2nd Annual MAS Jane Jacobs Forum "Re-Imagining New York: Designing Urban Farms to Feed our City", I found myself listening to a panel that was espousing the needs for food production within the fabric of our cities - preaching to the converted no doubt. By no means a completely novel idea, the design and practice of vertical farming was being touted as a saviour to a diminishing capacity to feed the world's population. Perhaps one of many solutions needed to address this growing problem, I see opportunity to 'right-a-wrong' in the commodification of enclosed balconies.

Many developers continue to take advantage of the exclusionary clause, that remains nearly unchanged, - a maximum of 8% of FAR, with an allowance for 50% enclosed - to construct enclosed balconies that are nefariously marketed as “dens”. These areas contribute to the purchase price of the unit eliciting the same value as interior floor area. Due to their physical construction and design guidelines, however, they often lack the legal ability or physical flexibility to renovate.

While some forward thinking individuals already treat the otherwise mundane enclosures like the "outdoor environments" they were intended; by nurturing plants in an environment with a reduced sensitivity to variable outside weather conditions, most resort to illegal conversions, or find solace in their found access to diminishing storage space. Serving a laudable goal of reducing noise pollution within urban residential units, the bigger picture of the value of "space" looms heavily on all of us, particularly when it is used in inefficient ways and that benefit the few.

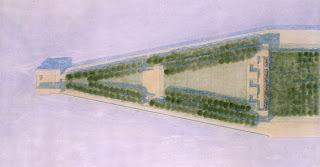

Is it possible that vertical farms may be right under our noses? Can we move beyond our youthful protestations in 'guerilla gardening' while still embracing the fostering of 'community gardening', and take charge of our own self-sufficiency and sustenance? While not all of us wish to, or are inclined to become farmers, gardeners, or plant enthusiasts, space design has the ability to influence and encourage these behaviours. If we can suspend judgement for just a moment, can we envision a typical residential tower that supports the dietary needs of its residents and the community?

Change is often incremental and begins with small steps. The 'Tipping Point', however, is viral and leads to paradigmatic shifts. It is not my intention to suggest that "enclosed balconies" are the panacea for Food Security Management (FSM) but it does strike me as worthy of exploration. Can developers still be incentivized to build for a future that ensures food security? Can we design buildings with site-specific open-spaces that respond to the needs of its inhabitants better - simultaneously managing desires for privacy as well as community? Can we achieve truly 'productive growth' in our existing and future vertical residences and still have a choice to participate in its bounty? I have no answers, only questions. At the very least we may spawn the emergence of a new built form.

(Typical Enclosed Balcony - Interior)

(Solarium Garden?)