No Good LEED Goes Unpunished

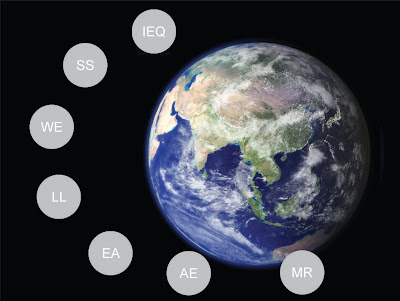

(LEED Categories of Assessment)

Ignoring uniqueness and genus loci, the suitability of design as it relates to place is institutionally swept aside in a consumptive effort to achieve a place on the LEED podium - bronze, silver, gold and in this global competition, platinum. Arguably, the addition of green systems to environments that do not need them is costly and wasteful. Also, such measures can often lead to a decrease in actual performance despite earned points on an assessments scorecard. A double-edged sword of sorts, LEED's strength as a universal application is also it's most egregious weakness. Sadly in a world of marketable ideas and quantifiable progress, a more sustainable approach may very well be lost to a more sale-able and semantically palatable unit of measure.

There are alternatives, however, forging new territory and providing hope for a more holistic system of accreditation. The Living Building Challenge (LBC) Standard, the Living Building Leader program, and changes to LEED itself have recently brought a sweeping rise of professionals seeking accreditation. Similar to what might be considered degree inflation, new LEED APs require additional testing and face increased costs a result. Arguably a more favourable and practical approach to sustainable design is that of the LBC v2.0 produced by the International Living Building Institute (ILBI). An "evolving tool" this new and increasingly popular standard seeks to move beyond the hermetic preclusions, and exclusions, of LEED to include a host of both infrastructure and landscape issues that combine to reflects more holistic approach to green design.

Eschewing the perpetuation of more built environments that perform only within the rigid measures of 'space', the LBC and other alternatives offer hope for the design of living structures and systems that are grounded in 'place'; reflecting a new ethos of spatial design and systems science that moves beyond 'Green' to include a much broader, more colourful spectrum of sustainability.

Eschewing the perpetuation of more built environments that perform only within the rigid measures of 'space', the LBC and other alternatives offer hope for the design of living structures and systems that are grounded in 'place'; reflecting a new ethos of spatial design and systems science that moves beyond 'Green' to include a much broader, more colourful spectrum of sustainability.